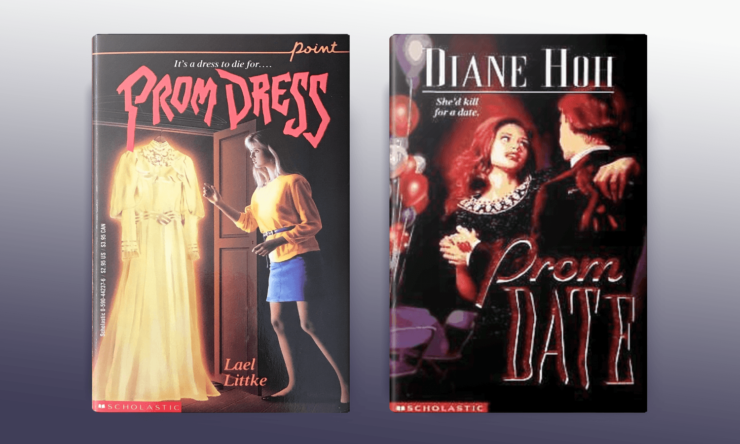

Prom night holds a privileged place in the annals of popular culture, depicted as a rite of passage, particularly for high school seniors who are getting ready to put their adolescence behind them, looking forward to graduation and their future beyond it. If high school is a four-year gauntlet of popularity contents and social peril, prom night is the final exam. Following in the tradition of Stephen King’s Carrie (1974) and the 1980 slasher Prom Night, Lael Littke’s Prom Dress (1989) and Diane Hoh’s Prom Date (1996) explore the potential horrors of the prom.

Both of these novels unsurprisingly foreground their female protagonists’ desperation to find the ideal date and the lengths to which they are willing to go to sabotage one another in their quest for a perfect prom night. The tagline of Hoh’s Prom Date reads “she’d kill for a date” and this teaser is literal, as a teenage girl attacks her competition one by one, hoping to free up the guy she wants to ask her to the dance. The idea that any of these girls might do the asking themselves, accept an invitation from the “wrong” guy (i.e. one of lower social standing), or even go to the dance solo is unfathomable. The driving force of this heteronormative romantic pairing is predictable and the young men over whom the girls fight aren’t particularly heroic or memorable, though they clearly communicate to these books’ teen readers what their top priorities ought to be.

While the romantic narratives of these novels aren’t especially inventive, Littke and Hoh’s descriptions of their girls’ prom dresses offer fascinating revelations about each girl’s individual personality, the competition between the girls, and perceptions of fashion and femininity in each novel’s respective moment.

In Littke’s The Prom Dress, the dress itself is the driving force of the narrative and the central feature of the book’s cover art, radiating from the center of the cover. Robin is new in town when she gets invited to the prom by Tyler, who is rich and handsome. In many ways, Robin is a refreshing teen horror heroine: she is a dancer and her commitment to dance comes first, as she practices endlessly and works to get a competitive college scholarship. She also has an afterschool job, working as a companion to an elderly neighbor lady named Miss Catherine, a job Robin has so that she can help support her family. Robin’s father is dead and she, her mother, and her little sister Gabrielle inherited a big, old house, which requires a lot of upkeep. From the outside looking in, Robin seems to have it all—a nice house in a desirable neighborhood and the “right” boyfriend—and several of her peers even assume that her family is wealthy and privileged, but these are appearances that Robin has to work endlessly to keep up and which ultimately prove untenable. In contrast, this level of privilege comes effortlessly to Tyler, who complains “Between your dancing and your working, I hardly get to see you. Where do I rate on your list of priorities?” (4, emphasis original). While Robin worries about losing Tyler if she can’t live up to his expectations, her dancing and her family unapologetically come first, making her an anomaly in the ranks of teen horror girls, most of whom are willing to sacrifice just about anything to please the boy they like.

Robin likes Tyler but worries that she may have to turn down his prom date invitation because she doesn’t have the money to buy the right kind of dress, worrying that her clothing—and by extension, Robin herself—will never be “good enough” to deserve him. Robin’s dreams (and nightmares) come true when she finds the “perfect” dress hidden in Miss Catherine’s attic. And never mind the fact that this is the one dress Miss Catherine told Robin she can’t borrow. Robin is in awe of the dress, with its “deep scallops of creamy lace. It had long sleeves and a high lace collar … [The dress] spoke softly of elegance and muted music and romance. It glowed in the dark closet as if it were lighted from within” (12). It seems an odd choice for the prom, conservatively old-fashioned rather than sexy and stylish, and proms aren’t particularly well-known for “elegance and muted music,” but Robin has her heart set on this particular dress and even though she’s a good girl, she lies to Miss Catherine and steals the dress to wear to prom (though it turns out this moral failing isn’t really Robin’s fault because the dress is cursed, everybody who sees it is irresistibly driven to steal it, and Robin’s fundamental goodness remains uncompromised, even if she does have to deal with the consequences of her actions).

Buy the Book

And Then I Woke Up

Robin has a real Cinderella moment, and the prom is everything she dreamed it would be, until she and Tyler are named prom king and queen, ascend a high, rickety staircase to their their thrones (which just seems like a really bad, structurally unsound idea, cursed dress notwithstanding), and the staircase collapses beneath them. Robin’s feet are crushed, the doctors don’t know if she’ll ever walk or dance again, and her hard-won scholarship may be potentially worthless.

While Robin is confined to her hospital bed, the dress continues to wreak havoc, promising other women their greatest dreams before corrupting them and robbing them of their most distinctive characteristics. A nurse named Felicia steals the dress from Robin’s hospital room closet as the perfect dress for an important dinner with her boyfriend, who is preparing to become a minister. The dinner is hosted by the dean, who writes make-or-break recommendation letters, and Felicia needs to look demure and refined, while faced with a miniscule budget and a hotsy-totsy wardrobe at home. The dress begins to squeeze the life out of Felicia, who disrobes and flees the party in a set of the dean’s wife’s stolen clothes, accidentally stealing the other woman’s jewelry as well, which is in a bag Felicia grabs to carry the dress. A teenage girl named Nicole finds the dress next in Felicia’s bag on a bus, and wears it for her high school quiz bowl banquet, where she is the star member of her team and hopes to impress her peers and seduce her teacher (a side plot that isn’t identified or unpacked as being as serious or problematic as it should be). While the seduction seems to be proceeding apace (gross), Nicole panics when she sees the police, thinking she’s about to be busted for stealing the dress and jewelry. Nicole flees, a statue falls on her head (a bust of Einstein balanced atop a wobbly pillar, yet another object lesson in the importance of structural integrity), and she ends up with amnesia, losing both her sense of self and her enviable intellect.

The dress’s final temptation brings the horror full circle, as Robin’s sister Gabrielle steals the dress, and attempts to steal Robin’s boyfriend Tyler, a betrayal which echoes the foundational curse of the dress and the violent feud between Miss Catherine and her sister Rowena, who threw acid on her sister’s face after Catherine went to the prom with Michael, the guy Rowena had set her own sights on. It also turns out that Miss Catherine is actually Rowena, who long ago murdered her sister and assumed Catherine’s identity, and Rowena is thrilled that the cursed dress has been out and about once more. When reporters track down down Michael, the young man whose fickle affections started this whole mess, their discovery is anticlimactic, as “His children said he’s never mentioned either Catherine or Rowena” (165), relegating the sisters to a silenced and dark episode in his past rather than some star-crossed lost love. What’s the point of fighting over a guy, betraying your sister, and having your face disfigured if he’s not even going to remember or talk about you?

But cattiness and corruption never go out of style and apparently, neither does this dress, which is picked up by an antique dealer before the house is torn down, displayed in her store, and stolen … again.

The fashions in Hoh’s Prom Date are more contemporary, with the teenage girls looking for glamour and sex appeal rather than scalloped lace and high collars. Margaret’s mother Adrienne owns Quartet, the most fashionable dress store in town, full of one-of-a-kind custom creations. The popular girls who ostracize and bully Margaret and her friends are some of Adrienne’s best customers. Stephanie is the queen bee of the popular girls’ group, Beth is kind to Margaret when she sees her on her own at school but sycophantic and complicit in Stephanie’s cruelty when the girls are together, and Liza is seems to be the nicest of the mean girls, chiding Stephanie to not “be such a pain. Mind your manners” (9). When they come shopping at Quartet for their prom dresses, the popular girls each find something perfect, with Stephanie “wearing the red dress, a short, slinky number with spaghetti straps. Liza was wearing black, and Beth looked lovely in a slender pale blue slip dress” (15). Even the girls who don’t plan on going to prom have their dream dresses all picked out, with Margaret’s best friend Caroline pining for a beautiful turquoise gown, as Margaret reflects that while Caroline might not be able to wear it, “it would crush her if someone else went to the prom in that dress” (14).

The dresses in Prom Date symbolize a range of power dynamics and negotiations. While Adrienne is the designer and the only one who actually works at Quartet, she has three silent partners who were her high school friends and who are now the mothers of the popular girls who shop in the store. No extended backstory is provided for this cohort of friends and Hoh never shows the reader any interaction between or communication among them, so there’s no way of knowing how close they were, what behind-the-scenes roles these other women may play, or how their dynamics may have shifted in the intervening decades between their own high school days and their daughters’ prom. The class disparities, however, are clearly demarcated, as the popular girls clearly don’t see Margaret as one of their own and treat Adrienne as a service person rather than as a family friend. Adrienne is the one responsible for the four women’s collective success with Quartet, but she’s relegated to a lower class and social position because she’s the one who is doing the work, while the other women enjoy lives of leisure filled with society events and gardening (and maybe attempted murder when some of their gardening chemicals are used in a poisoning, though the moms are ultimately cleared of suspicion). Quartet and the dresses continue to be the epicenter of power struggles between Margaret, Catherine, and the popular girls as well, as the girls’ dresses are violently destroyed shortly after they buy them. When Margaret finds the dresses in the alley, what she finds is unsettling: “a red silk dress with spaghetti straps, one of them ripped away now, the dress so soaked with mud, the bright red had become dark brown. Beneath that, a black dress, strapless, its bouffant skirt flattened into a thick pancake by car tires. And on the bottom of the fouled mess, something pale blue … Ruined, all of them, ruined beyond repair” (19). Another dress mysteriously disappears and Margaret is nearly murdered a couple of times, first locked in a dumpster that is then set on fire, and, later, attacked in her mother’s sewing room above the store.

The dresses and prom are a point of contention between all of the girls. Stephanie tells Liza that pastel colors suit her better to steer the other girl away from the red dress Stephanie wants for herself, and Margaret’s best friend Catherine views Margaret’s plans to go to prom as a personal betrayal, wanting Margaret to stay home with Catherine and their other friends. Prom brings out the worst in all of the girls: Catherine becoming a classist snob who would rather go to prom with a popular guy she barely knows than a less popular one who treats her with kindness and respect. The girls swoop in like vultures after each new disaster, angling for a date with the victimized girls’ boyfriends. They all suspect one another of murder, friends and enemies alike. Liza is revealed as the greatest danger, however, willing to do anything or hurt anyone to ensure she gets the prom night she wants: she leads Stephanie to the top of a dilapidated lighthouse by telling her she saw Stephanie’s boyfriend there with another girl and she makes sure Stephanie “falls” from the lighthouse when the rusted railing breaks. She attacks Margaret, trying to poison her, set her on fire, and stab her. She attacks another one of her friends, Kiki, hitting her in the face with the prom fund cashbox, certain that Kiki will be too embarrassed to show her battered face in public, and will break her date to the prom, freeing up another eligible bachelor.

When Liza shows up at the prom—arrested for Stephanie’s murder but out on bail—her clothing and appearance are the dominant indicators of how much has changed and who she has become. While the black dress Liza chose at Quartet was stylish and sexy, the dress she wears when she shows up at the prom is “full-length, long-sleeved and matronly, and at least two sizes too large. It hung on her like a sack, and one shoulder had slipped off, causing the dress to hang at an odd angle around her neck” (267). The dress is her mother’s, again drawing parallels of fashion and popularity between these mothers and daughters, though in this case, Liza’s attempt at an idealized image is corrupted, a performance driven by desperation. Liza’s makeup is exaggerated and unevenly applied, and she has made herself a prom queen crown out of stapled cardboard and tinfoil, a monstrous parody of femininity as she refuses to relinquish her dream of the prom.

This spectacle becomes even more sensationalized as Liza projects this fantasy onto her peers, who view her with pity rather than fear, anger, panic, or exclusion. Liza asks Margaret’s date Mitch to dance with her and as their classmates and Liza’s parents look on, “Mitch led Liza, in her bizarre garb, out onto the dance floor …. Liza lay her head on Mitch’s chest as he spun her slowly around the floor. For those brief moments, at least, all of the rage and the hatred seemed to have drained out of her, and she looked content” (270-271). However she may look and however others may see her, in her own mind, Liza is wearing a beautiful dress and having the prom of her dreams. While the dress itself is the central focus of Littke’s Prom Dress, Hoh’s cover depicts this fractured resolution, with Liza in her ill-fitting dress, smeared lipstick, talon-like fingernails, and a concealed murder weapon in the hand she has wrapped around Mitch’s shoulders (which is a bit baffling, given that Liza never used a murder weapon, simply kicking at Stephanie’s hands until she lost her grip on the lighthouse post and plummeted to her death). While teen horror covers rarely offer visual representation of the novel’s resolution, instead opting to depict images of suspense and danger so as not to give the mystery away, this cover makes a spectacle of Liza’s disarray, an exaggerated and dangerous image of performative femininity. Though this is an unconventional cover choice, it echoes the fact that Liza’s peers are more taken aback by her appearance in this moment than they seem to be about the murder and attempted murders she has committed.

After this one dance with Mitch, Liza says she’s tired, she goes home, and the prom quickly rebounds to its pre-Liza revelry, as “spirits lifted again and their fun resumed” (273), despite Liza’s appearance, the murder of one of their classmates, and the violent attacks on several others. After all, the prom must go on.

What happens after the prom remains a mystery. In Prom Dress, Robin and Gabrielle will have some serious work to do in rebuilding their relationship after Gabrielle tried to steal Tyler from her sister. The other girls who fell victim to dress’s powers will take a while to recover as well: Felicia has lost her boyfriend and has to regain her sense of self, now that she has been tested and has found she wasn’t as morally incorruptible as she believed herself to be, while Nicole’s memories may or may not come back. In the final pages of Prom Date, Margaret tells her new boyfriend Mitch that she and her friends are “a package deal” (274) and that her loyalty to and camaraderie with them is of non-negotiable importance. However, their relationships have been marred by Catherine’s jealousy about Margaret going to the prom, as well as Margaret’s suspicion that Catherine might be the murderer and her public shaming of Catherine and the rest of their friends for trying to poach the murdered and injured girls’ prom dates, including their attempts to pick up Stephanie’s boyfriend Michael at Stephanie’s funeral reception. These realizations—that one’s friends could be so callous, that someone you’ve known and trusted all your life could be a murderer—are hard to bounce back from and none of them will ever really see her friends in the same way she did before.

Prom Date opens with a prologue of four nameless girls pledging their loyalty and eternal friendship to one another—Margaret and her friends? Adrienne and hers? A symbolic representation of both groups of girls and a general reflection on the nature of female friendship? Hoh holds out on her readers here, though she does end her prologue with the ominous reflection that while these girls fervently believe they will be friends forever, “They would have been wrong” (3). While both Prom Dress and Prom Date end with idealistically repaired relationships, the end of prom season is not a reset, and these young women won’t be able to discard their animosity and fear with their wilted corsages.

Alissa Burger is an associate professor at Culver-Stockton College in Canton, Missouri. She writes about horror, queer representation in literature and popular culture, graphic novels, and Stephen King. She loves yoga, cats, and cheese.